The American news media has been working overtime to convince people that violent crime is dramatically falling. Here are typical headlines from ABC News and NPR.

“US stats show violent crime dramatically falling, so why is there a rising clash with perception? ‘I don’t believe the statistics,'”‘ said Auriol Sonia Morris, a Trump supporter.”

Bill Hutchinson, “US stats show violent crime dramatically falling, so why is there a rising clash with perception?,” ABC News, March 22, 2024

“Violent crime is dropping fast in the U.S. — even if Americans don’t believe it”

Karen Zamora, Ari Shapiro, and Courtney Dorning, “Violent crime is dropping fast in the U.S. — even if Americans don’t believe it,” NPR, February 12, 2024.

Murder plummeted in the United States in 2023 at one of the fastest rates of decline ever recorded, Asher found, and every category of major crime except auto theft declined.

Yet 92% of Republicans, 78% of independents and 58% of Democrats believe crime is rising, the Gallup survey shows. . . .

Ken Dilanian, “Most people think the U.S. crime rate is rising. They’re wrong.” NBC News, December 16, 2023.

NBC and NPR pointed out that the murder rate in 2023 was lower than in 2022. Unfortunately, their discussion ignores that the murder rate was still 7% above where it was in 2019.

The news media often focuses on the initial murder rate data, though the ABC News article and others looked at the FBI’s 2022 violent crime data, which points out that violent crime reported to police declined in 2022.

But, there is a big problem with using the FBI Uniform Crime Report data on crimes reported to police because victims don’t report most crimes (UCR data available here). More importantly, the number of crimes reported to police falls as the arrest rate declines. If people don’t think the police will solve their cases, they are less likely to report them to the police. While the violent crime rate reported to police fell by 1.7% between 2021 and 2022, the National Crime Victimization Survey shows that total violent crime (reported and non-reported) rose from 16.5 to 23.5 per 100,000 — a 42.4% increase (Links to the NCVS are available at the bottom of this page). Violent crime in 2022 was above the rate the last year before the pandemic in 2019 and above the average for the five years from 2015 to 2019.

This divergence arises for several reasons. In 2021, 37% of police departments stopped reporting crime data to the FBI (including large departments for Chicago, Los Angeles, and New York), and others are underreporting crimes. But also because of the dramatic decline in arrest rates.

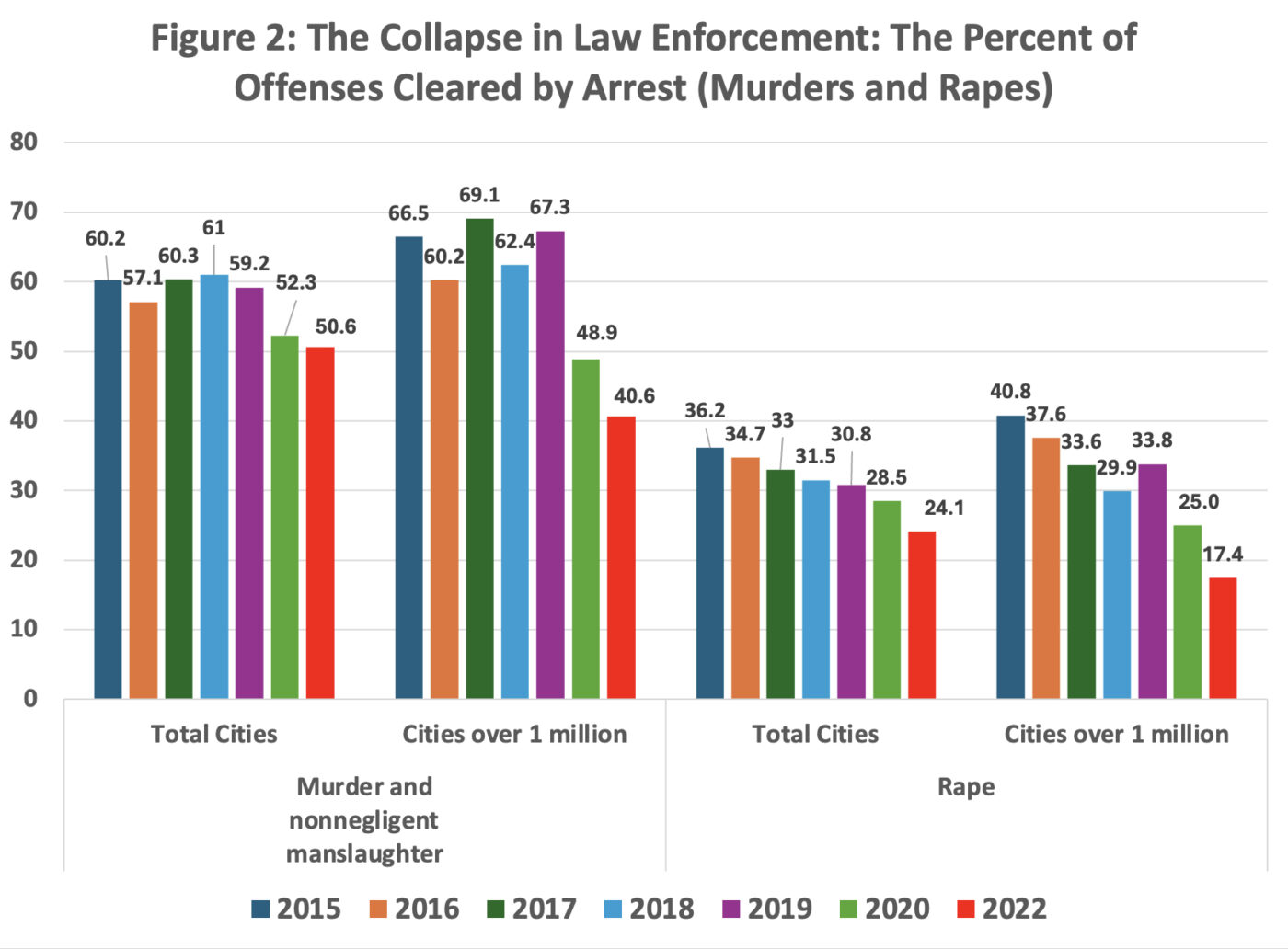

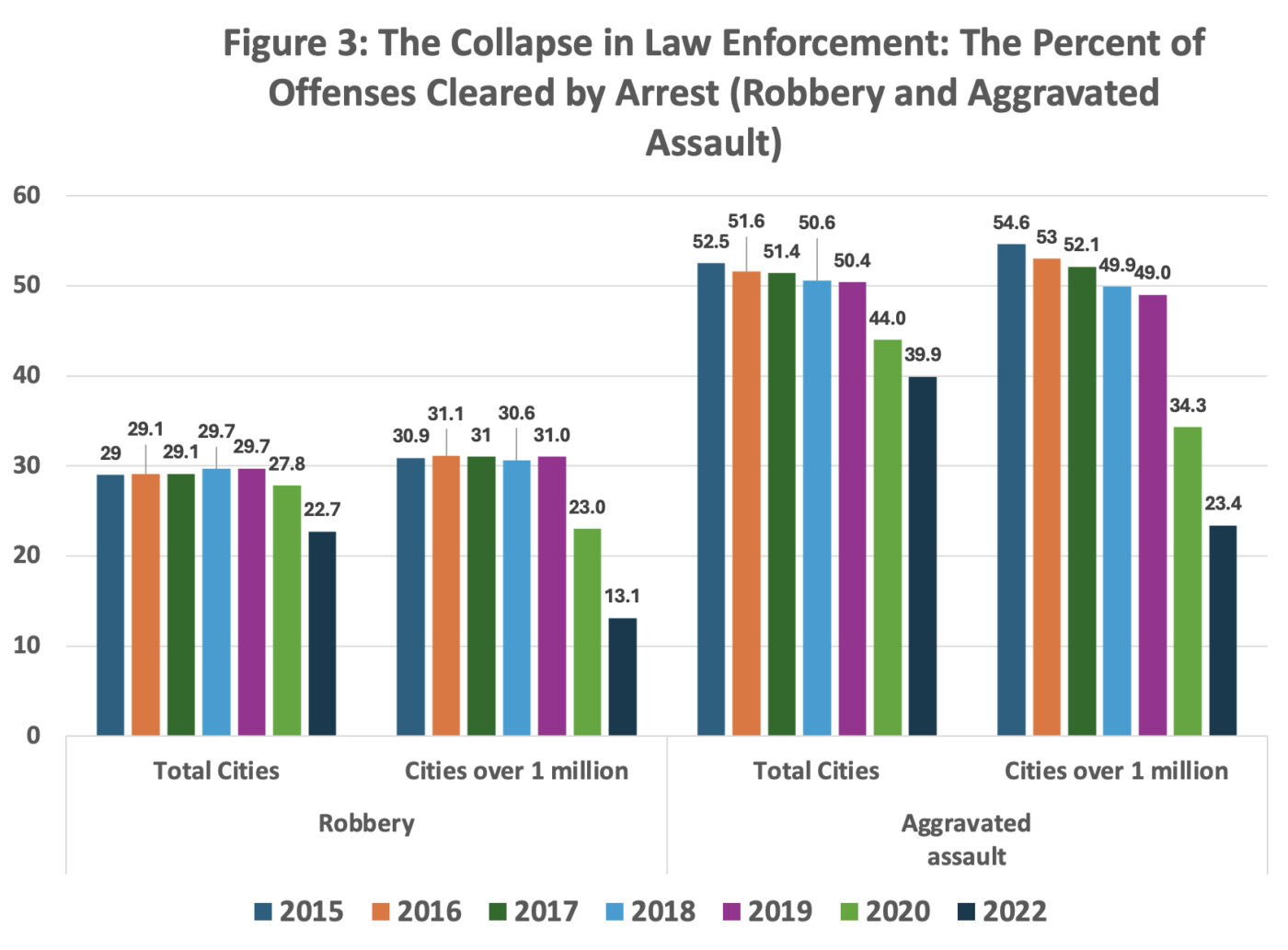

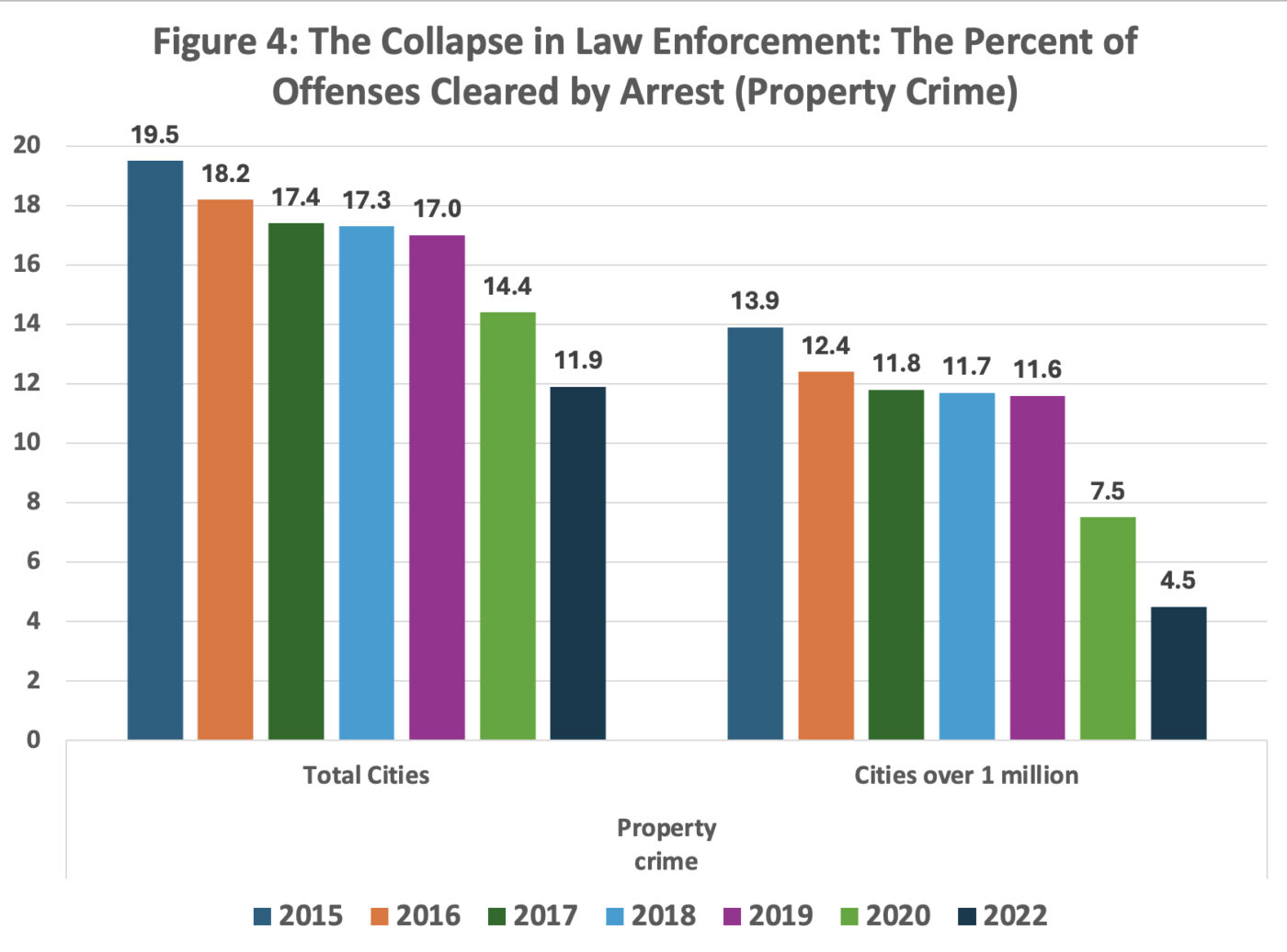

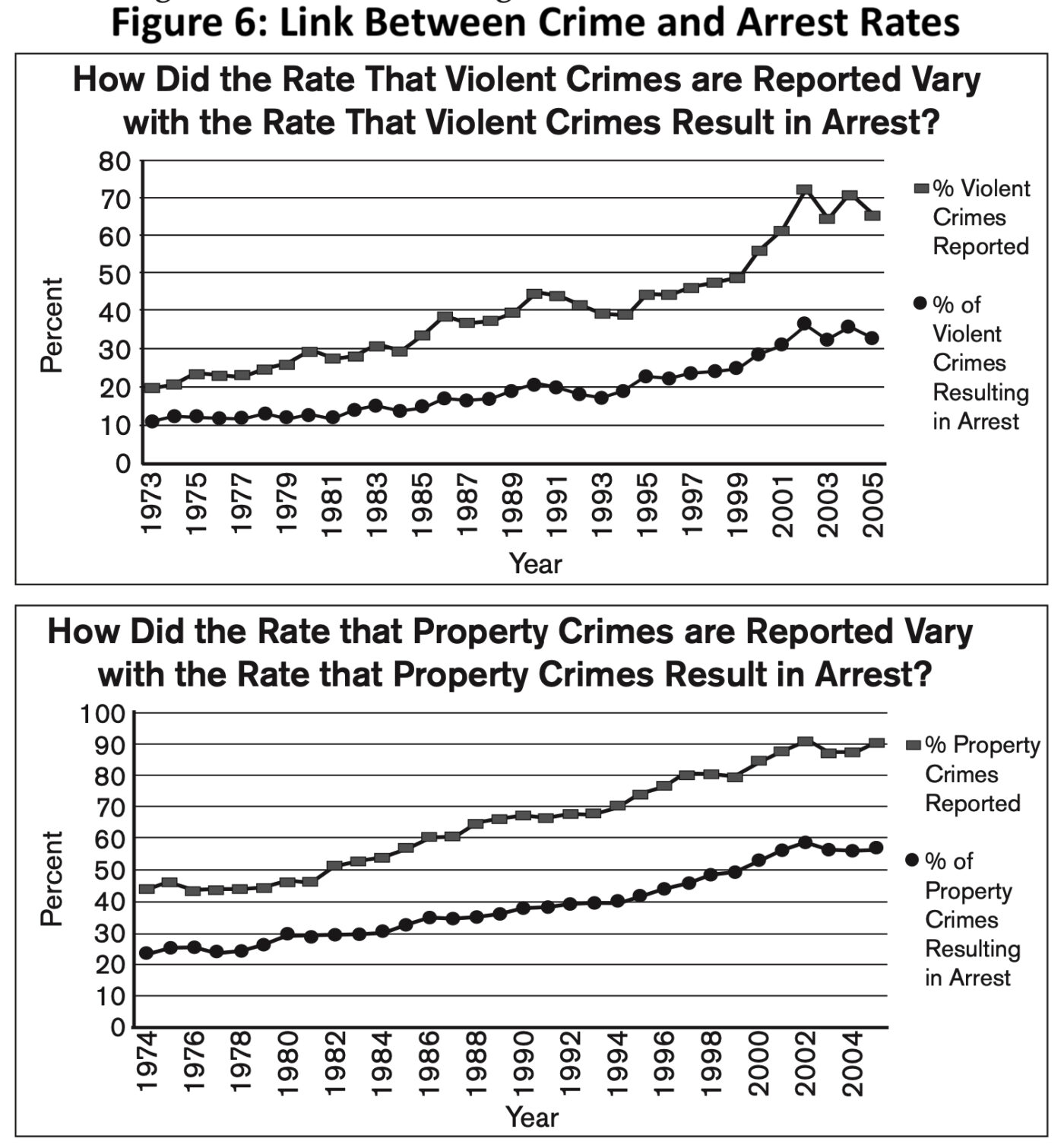

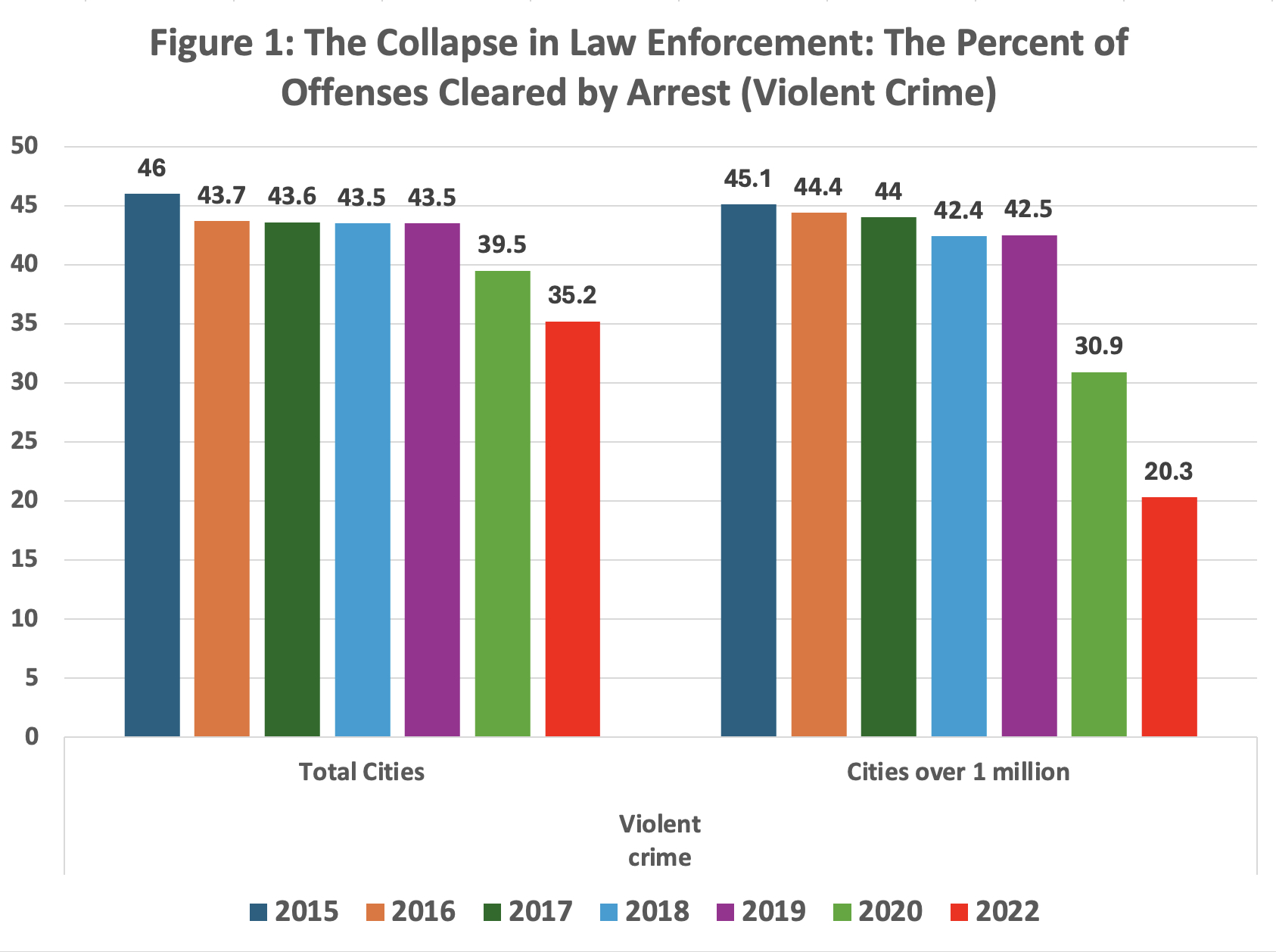

Figure 1, presented at the top of this post, illustrates the dramatic drop in arrest rates for violent crimes reported to the police. If you compare the last five years before COVID-19 to 2022, the arrest rate for violent crime across all cities fell by 20%. But for cities with over one million people, it fell by 54%. The drops in arrest rates by type of violent crime ranged from 15% to 27% for all cities and from 38% to 58% for cities with more than one million people (Figures 2 and 3). Figure 4 shows the sudden drop in arrests for property crimes that started in 2020. Comparing the five years from 2015-2019 to the arrest rate in 2022 shows a drop of 33% for all cities and a 63% decline for cities with more than a million people. All the data is in the Excel available here.

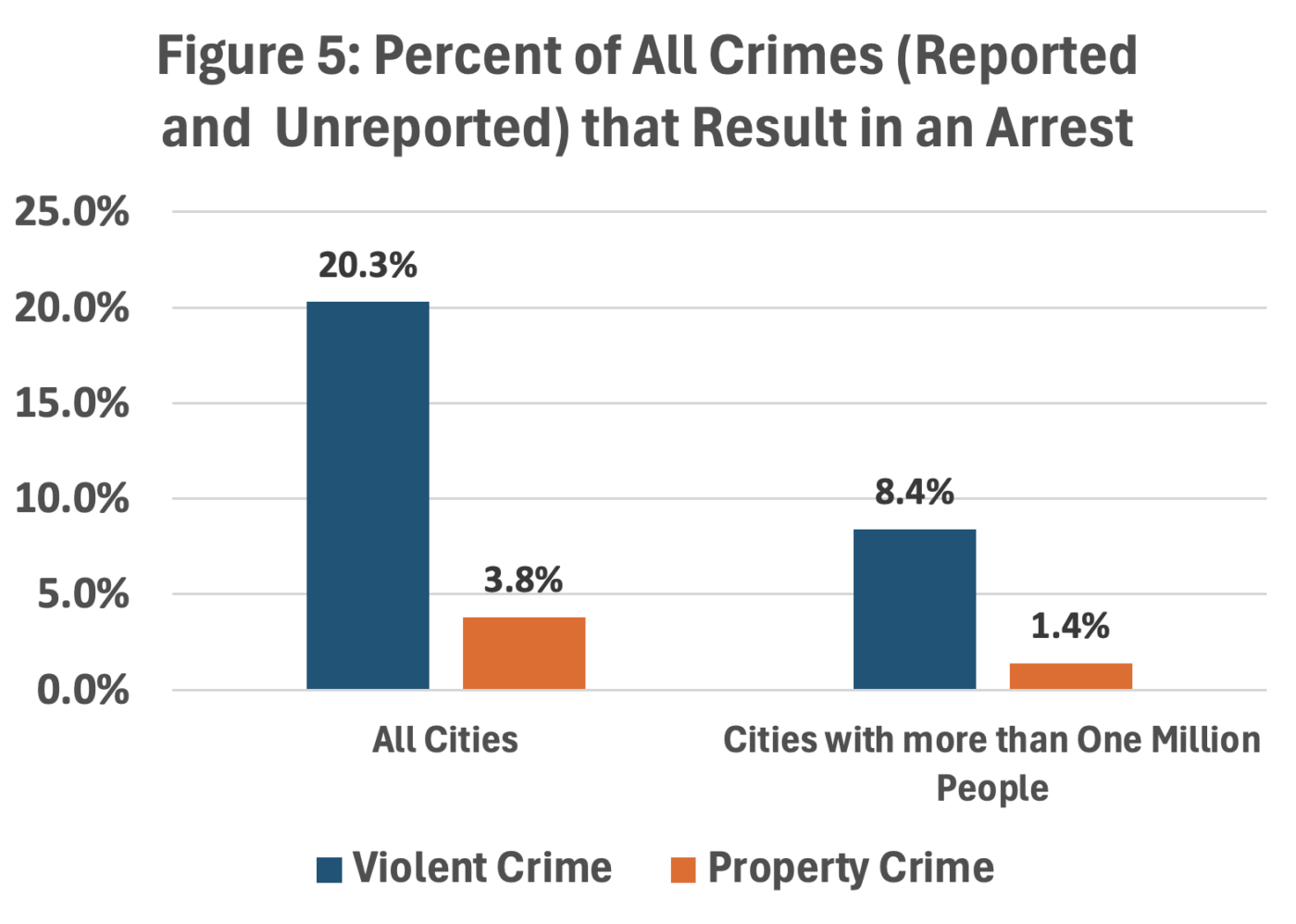

To get another idea of what these numbers mean, in 2022, with 41.5% of violent crimes reported to the police and only 35.2% of those resulting in an arrest, that implies that only 14.6% of violent crimes result in an arrest (Figure 5). If you take the 20.3% of reported violent crimes in large cities resulting in an arrest, that implies that only 8.4% of all violent crimes resulted in an arrest. For property crimes, the numbers are even worse. With 31.8% of property crimes reported to police and only 11.9% of those reported crimes resulting in an arrest, that means that only 3.8% of all property crimes result in an arrest. For large cities with over a million people, only 1.4% of all property crimes result in an arrest.

The notion that the rate at which victims report crimes to police closely tracks changes in arrest rates has long been understood. For example, Figure 6 shows the relationship for violent and property crime data from 1973 to 2005 (source: Freedomnomics, 2007, p. 115).

The National Crime Victimization Survey data is available here.

https://bjs.ojp.gov/document/cv22.pdf

https://bjs.ojp.gov/content/pub/pdf/cv21.pdf

https://bjs.ojp.gov/sites/g/files/xyckuh236/files/media/document/cv20.pdf

https://bjs.ojp.gov/content/pub/pdf/cv18.pdf

Thank you for all of this Dr. Lott. I look forward to your newsletters!

I looking at the data, can you please let me know why the charts exclude 2021? Thank you.